Popular perception of a place doesn't always align with geographical accuracy, as a long history of psychic, or conceptual, mapping has taught us. To wit: New Yorkers consider their city to be the center of the universe, despite the fact that, as author and activist Rebecca Solnit puts it, it's "dangling like a pendant off the bottom of New York state."

Nevertheless, Nonstop Metropolis, Solnit's latest book with the geographer Joshua Jelly-Schapiro, puts New York at its center, and explores the history, culture, infrastructure, and diversity of residents that make the city what it is. The book rounds out a trilogy of atlases–including San Francisco's Infinite City and New Orleans's Unfathomable City–that collect maps and corresponding essays from some of the city's best writers, artists, and thinkers.

From a subway map that charts out the city's famous women residents to a map of the unlikely wildlife in the city, the book explores "what maps can do to describe the ingredients and systems that make up a city and what stories remain to be told after we think we know where we are," Solnit writes in the introduction.

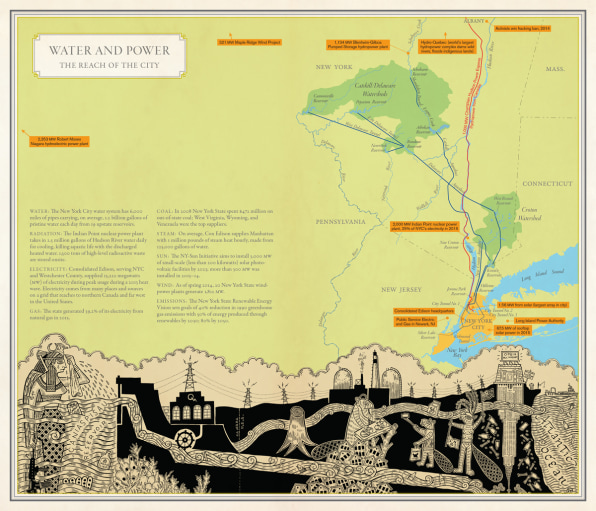

Many of the book's maps and essays reveal the invisible mechanisms that keep the city going. In Heather Smith's essay "Thirsts and Ghosts," for instance, the writer pinpoints where its water comes from, including the 85-mile-long Delaware Aqueduct built in the early 1900s. Today, Smith writes, the aqueduct has fallen into such disrepair it spills the amount of water needed for 500,000 people every day, "watering a phantom metropolis north of the city." A subterranean "shadow city" of tunnels brings water into New York City, and electricity comes in from as far away as a hydroelectric plant in a Canadian forest. The accompanying map plots the 19 upstate reservoirs that provide the city with water, as well as its sources of electricity, gas, and more.

The human level of the city's infrastructure is captured in an essay by the book's editor-at-large, Garnette Cadogan. It begins with him in the Hasidic neighborhood in Williamsburg, switching on the lights for a rabbi and his family at their home during Shavuot. The experience with these strangers kicks off a 24-hour walk around the city, during which Cadogan reflects on the diverse immigrant populations that make up the margins on the city.

In the city's schools alone, over 176 languages are spoken, according to the writer Suketu Mehta in his essay "Tower of Scrabble," a fascinating linguistic tour through the polyglot neighborhood of Queens. New York is a "sort of language asylum," writes Mehta, where immigrant enclaves allow banned and endangered languages to flourish. These and other maps document what fuels the city in a more abstract sense.

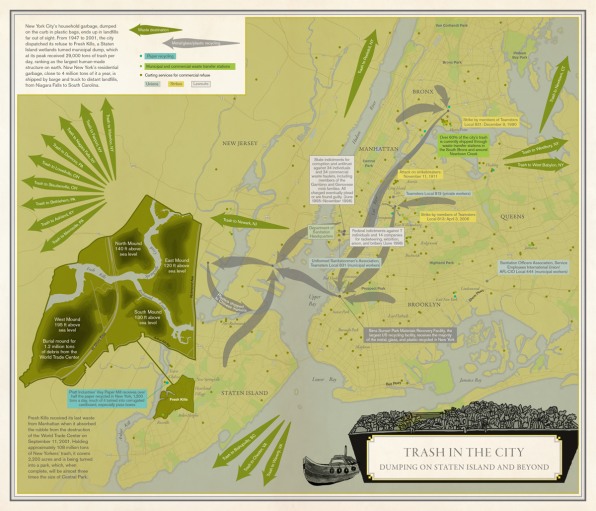

Lucy P. Lippard's essay "Coming Clean," which accompanies a map of Trash in the City, deals with the city's buried refuse–the byproduct of all the infrastructure, production, and diversity of inhabitants detailed in the rest of the book. She charts a path from the city to Fresh Kills in Staten Island, a landfill that at its peak received 29,000 tons of garbage per day before Rudolph Giuliani ordered its closing in 2001 as a thank you for the support of Staten Island residents during his mayoral election. Though the site is named for the Dutch word kille, or riverbed, Lippard notes that the "name suddenly took on a tragic sense" after 9/11, when personal effects and human micro remains were transferred there from Ground Zero.

Today, Fresh Kills is being transformed into a park by High Line architect James Corner, and its underground methane will provide enough energy to heat 20,000 homes, making the site an "ironic sanctuary from the climate effects its inefficient history has helped to produce," writes Lippard.

Lippard also notes that "garbage out offers a way of looking in" to the city; our unwanted items have a way of speaking volumes about who we are and how we live. As with most of the maps in the book, the accompanying Trash in the City map uncovers this unseen side of the city (including the nine out-of-city landfills where Fresh Kills' load has been redistributed).

Little goes unexplored in the experimental geographies and fascinating social histories that make up Nonstop Metropolis. Even in a place as heavily mapped and culturally familiar as New York City, there's still plenty of unchartered territory.

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/3065203/mapping-the-new-york-city-no-one-ever-sees

Posted by: sarisarimardirosiane0277983.blogspot.com

Post a Comment